We are sixteen years past the price peak of the 2000s housing bubble and people are still coming up with explanations for those outcomes while ignoring really basic and easy to find and verify facts. Arnold Kling links to this post here which includes the statement

What makes things especially tricky for the Fed is that the housing market is much less liquid than other major assets like stocks or bonds. It takes a couple of months for someone to sell their home, and then another month or two for sales to be reflected in national statistics. As a result, home prices tend to have more momentum than other assets. Once prices start to fall, they tend to keep going in the same direction.

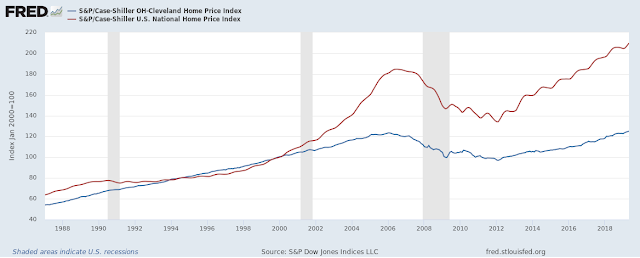

The use of the term momentum here is bizarre, and requires a very strange definition to allow it to be correct. Using Case-Shiller housing prices peaked in 2006 and bottomed in 2012, but the term momentum doesn't describe the action at all. The fall was steady at first, accelerated during the second half of the recession and then was slow with multiple upturns for the final 2 years.

We see 3 false bottoms during the final 3 years of the decline. The behavior after the peak is a fairly straight forward story of supply and demand: During the run up in prices* supply was outstripping demand as to much housing was built. The evidence here is simple- vacancy rates were rising as prices were rising

At the peak we didn't just have to much housing supply there was a pipeline of unfinished projects which were in some phase of starting but not completed that were put on hold. As prices started to stabilize those projects were completed, boosting supply and damping down prices again. We can see that in the starts minus completions data

Starts logically have to precede completions but from 2006 to 2011 the US was finishing hundreds of thousands of more units than it started. This is the tail end of the overbuilding that was occurring during the mid 2000s, and the price bottoms very shortly after we have burned through that overhang in 2012 where completions are dominated by starts again. A straightforward supply and demand rebalancing gets us most of the way to understanding the price action after the peak in 2006.

We have no such clear market behavior right now. The eviction moratorium and stimulus checks have skewed demand making the very low vacancy rates difficult to trust. I can confidently say that those two things are pushing housing demand higher but the magnitude is not easy to pin down. What ever the outcomes today they won't be driven by the same factors as occurred in 2006, and certainly not by vague assertions of 'momentum' based on how long it takes for a house to list and sell.

*This explanation is skipping over the how of increasing prices in concert with increasing supply which is the more interesting question.